What would the late former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker have thought about digital currencies issued by central banks?

The short answer is nobody knows; Volcker never really got steeped in the fast-developing world of crypto.

“Bitcoin? What’s that?” Volcker replied when asked about the largest cryptocurrency by a Quartz reporter in April 2013. “I’m too old to know anything about that.”

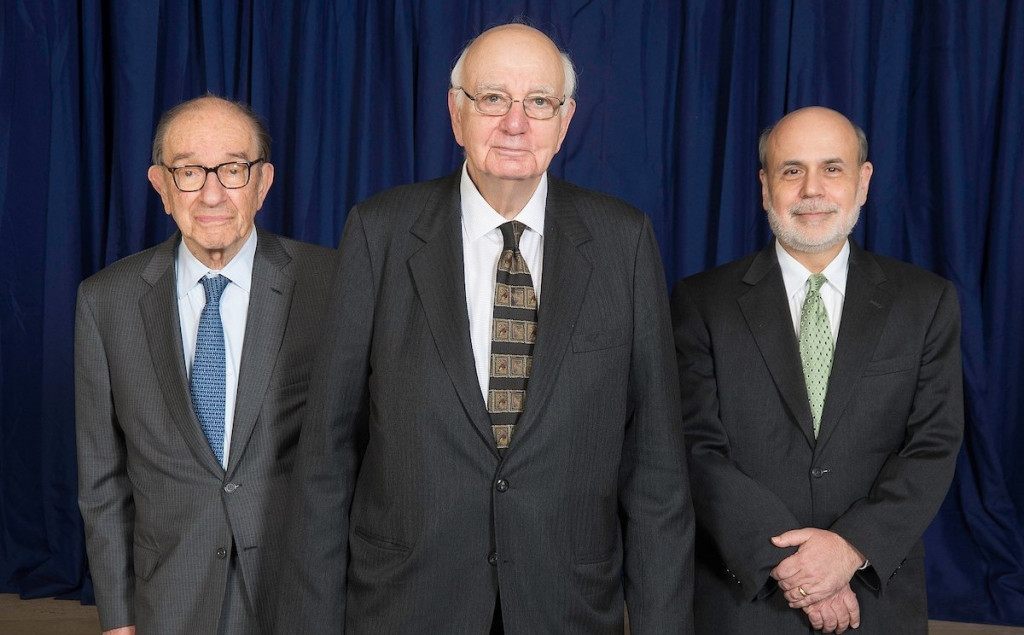

The question is worth asking, though, since Volcker, who died this week at 92, is regarded as perhaps the most effective and credible Fed chief of the past half century.

Volcker led the U.S. central bank from 1979 through 1987 and is known primarily for jacking up short-term interest rates to as high as 20 percent to short-circuit double-digit inflation. The aggressive move helped to push the U.S. into recessions in the early 1980s, driving the unemployment rate to nearly 11 percent from 6 percent and drawing outcry and pushback from corporate executives, unions and lawmakers. But by the mid-1980s, the inflation rate dropped back below 2 percent, and the economy resumed its growth.

Now, the Fed and central bankers around the world are grappling with the emergence of a new form of money: digital currencies made possible by cryptography and advances in the distributed-ledger technology known as blockchain. Authorities from Ghana to Sweden are examining the concept while China, the world’s second-largest economy, is moving forward with tests of a digital version of its national currency, the yuan. Some observers of say China’s effort might be partly geared to undermine the U.S. dollar’s supremacy.

Easier on consumers

The promise of these government-backed digital currencies is that they might reduce the need for paper bills and coins, making it easier for consumers and businesses alike to exchange payments. Those are benefits that Volcker likely would have embraced, says Richard Sylla, a New York University economics professor emeritus who specializes in financial history.

“One of the arguments for digital currencies is that it could lower the costs of moving money around the world,” Sylla said in a phone interview. “And he certainly wouldn’t have been against investigating the possibility of that.”

Sylla, who knew Volcker professionally, says he was with the former Fed chief once when he was about to fly to Mexico for a meeting. According to Sylla, Volcker casually remarked that the world might be better off if it had a single currency; things might just be simpler that way.

Of course, the U.S. dollar serves as the de facto global reserve currency, stockpiled by central banks and investors in just about every country. The U.S. is the world’s largest economy, and the dollar serves as the default tender for many cross-border loans as well as payments in international trade and big global commodity markets like oil and gold. There’s also the need for dollars to buy dollar-denominated assets like U.S. Treasury bonds, seen as a better store of value than risky assets like stocks in an economic downturn or financial crisis.

Volcker was a critic of Wall Street financial-engineering products like credit-default swaps and collateralized loan obligations, and he famously pushed (successfully) after the 2008 crisis to stop banks from making speculative proprietary trades with customer deposits.

But Volcker was reportedly a fan of technological improvements to make the financial system work faster and more efficiently, or to improve the ease of payments in the broad economy. Volcker said in December 2009 that he thought the ATM machine was the most important innovation in the banking industry of the prior two decades, because it “really helps people and prevents visits to the bank and it is a real convenience.”

'Volcker would have created it'

Dick Bove, a five-decade financial-industry analyst for the brokerage firm Odeon Capital, said in a phone interview that Volcker likely would have opposed bitcoin and other digital assets built by independent developers. According to Bove, Volcker believed that “central banks should have control of the financial system in a given nation, and it should have control of interest rates and the volume of currency being created, and it should be used to help the country meet whatever goals are needed at any point in time.”

But a digital currency issued by the central bank? Bove bets Volcker would have been all for it – just for the sake of keeping up with new technology.

“If the need for a central bank digital currency arose, I think Volcker would have created it,” Bove said.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said last week that he and the current Fed chair, Jerome Powell, agree there’s no need for a digital version of the dollar “in the near future, in the next five years.”

Paul Brodsky, a partner at the crypto-focused investment firm Pantera Capital, said Volcker likewise might have taken a cautious approach to a digital dollar rollout.

“He would have waited and let it see how it played out in the private sector before pushing forward with a Fed digital currency,” Brodsky said.

Keeping a tight lid on money...

Jimmy Song, with crypto-focused venture capital firm Blockchain Capital, says Volcker might have endorsed a digital dollar as a technology. But that leaves unsolved what Song sees as the basic problem that led to the original formation of bitcoin, in the wake of the 2008 crisis: technocrats’ efforts to exercise too much control over money, leading to mistakes and excesses.

Volcker is “not someone who wanted to give people self-sovereignty or freedom,” Song said in a phone interview. “A Fed-backed digital currency is conceptually not very different from the system that he oversaw. It’s mainly just an infrastructure upgrade.”

...but not too tight

David Yermack, chair of New York University’s finance department, said the late Fed chief was surprisingly conservative when it came to the benefits of limited government. One benefit of some digital-dollar proposals is that individuals might be able to deposit money directly with the Fed, without having to set up accounts at commercial banks.

But that might create the “risk of abuse for political reasons,” since the government would have more direct control over people’s money, says Yermack, who teaches courses on bitcoin and has co-authored research papers on central-bank digital currencies. Some critics of China’s push for a digital yuan argue that it would simply become easier for central authorities to monitor citizens.

The benefits of a central bank digital currency “might be desirable but encroach on personal freedom,” Yermack said. Volcker “had a lot of faith in the private sector. He was never a person who stressed big government for its own sake.”

But according to Sylla, the financial historian, Volcker would not have wanted to cede monetary authority to private companies like Facebook, which is developing a digital asset for payments, known as Libra.

“What Volcker would have said if he were still with us and we could ask him, is that the idea of a central bank digital currency was an idea worth studying, but I’m pretty certain he would not want it to be under the control of Mark Zuckerberg,” Sylla said, referring to Facebook’s CEO.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Yermack knew Volcker. That reference has been removed.